Recently I have started reading the book Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World-- and Why Things Are Better Than You Think by Hans Rosling.

I won’t lie, the recent weeks have been a bit of a rollercoaster for me working with some uncomfortable anxieties about the latest round of online learning, and in my search for a new book to read I came across this book and hoped it would provide some much needed relief from the barrage of scary news every day. Factfulness, as the title might imply, seeks to demonstrate (through facts) that the world is indeed getting better not worse.

I understand that this book was published pre-pandemic, but the core of this book and many of the examples given within remain and ring true.

One sentence that really stuck out for me (and served as the inspiration for writing this post) was related to how we can control the ‘negativity instinct’, that which even when faced with facts and information that things are getting better, our instinct is to believe that things are getting worse.

In helping to combat this instinct, Rosling explains that it is useful to persuade ourselves to keep two thoughts in our mind at the same time, this is to not balance out negative news with positive news, or to tell ourselves ‘don’t worry, relax’ or to ‘look away’ from problems, but rather that ‘things can be both bad and better’.

‘Bad and better’... that sounds interesting!

The analogy that Rosling uses is to think of a premature baby that is in an incubator and experiencing serious health problems. Whilst in the incubator, their breathing rate, heart rate and other important signs are tracked so any positive/negative changes over a week can be seen. After a week or so, this baby may have improved according to a lot of these measures, and may be getting better, however they remain in an incubator because they are still in a critical state. In this sense you can say that the baby’s situation is improving, agreed. You can also say that the situation is still bad, also agreed. By saying things are improving is not to say that things aren’t bad, and actually it isn’t really helpful to choose between describing a situation or event as bad or better. They can be both at the same time.

This particular passage got me reflecting on my observations of trying to start my new blog and joining social media to share posts and thoughts through the WISEducation lens. What struck me was some of the comments on social media surrounding wellbeing in schools. Comments that reflect views (apologies for the simplification here) that teachers are overloaded and burned out, and therefore don’t have the capacity or the time to also have to think about wellbeing. Other types of views reflect the rhetoric of ‘I am employed to teach [insert subject here], I’m not a counsellor or a social worker… they should be the ones teaching this’. To insert a disclaimer here, these are not views representative of most of the people I follow or have engaged with in the teaching profession, that would be selling those teachers incredibly short. I understand that these are the minority but interestingly these are even views that I have heard in person. This is also not to say that people can’t have this view, or that it is wrong. I completely understand that teachers are under an enormous amount of pressure; parental expectations, managing behaviour, achieving top grades, workload, adapting teaching during lockdown and the knock-on impact on teachers’ personal lives - there is a lot to contend with. Rather I would like to share some thoughts which may allow space to think about this slightly differently, and in doing so consider the ways that ‘wellbeing’ can become less of a ‘new-age add on’ (to be slightly crude) and time consuming, and actually as something that has been embedded in teaching for a long time and that could hopefully make our lives, and the lives of those in the communities that we serve, both better and more efficient.

Has wellbeing in schools come full circle?

One point I’d like to give attention to is the notion that schools and the roles of teachers have long been underpinned by a form ‘wellbeing’.

A report compiled by Banerjee et al. (2016) entitled ‘Promoting Emotional Health, Well-being and Resilience in Primary Schools’ provides a brief history of the approaches to wellbeing adopted by schools in the UK. Best et al. (2000, as cited in Banerjee et al., 2016) contend that work related to wellbeing was considered to be a part of the teachers general role up until the 1960s.

In this regard, teachers were involved in students personal, social and emotional development, as well as their cognitive development more broadly. According to Banerjee et al. (2016), these individual efforts to support a more holistic approach to the development of their students was complimented by school pastoral systems such as the use of tutorial or homeroom groups, and the introduction of additional staff such as educational psychologists and classroom assistants - measures that are still very much in existence today.

However, the authors explained that ‘the role of the teacher has largely changed from the wider, more generalised role to one more focused upon cognitive/academic development.’ (Banerjee et al., 2016, p. 10). These shifts occurred within the context of educational policy changes, as well as parallel discussions of concerns about teacher workload. This shift to a more ‘academic-focused’ teacher role was formalised by the National Union of Teachers in 2003, which in turn ‘had the unintended consequence of subtly transforming the teaching role to one more focused on the teaching of ‘core’ academic content’. Despite this shift there is still the prescription that teachers should ‘promote the safety and well-being of pupils’ (NUT, 2003, as cited in Banerjee et al., 2016).

Regardless of the narrowing focus on achieving academic outcomes, it is clear that schools still serve as important social context and play an integral role in shaping the lives of young people with regards to their social and emotional health and wellbeing. In relation to this, Resnick (2005, p. 398, as cited in Banerjee et al., 2016) argued that schools should be involved in the “intentional, deliberative process of providing support, relationships, experience and opportunities that promote positive outcomes for young people.”

An interesting article to bring into this discussion is by Calvert (2009) entitled, ‘From ‘pastoral care’ to ‘care’: meanings and practices’. The term ‘pastoral’ here can be seen to be an umbrella term to incorporate wellbeing and is defined by the author as ‘the term used in education in the United Kingdom to describe the structures, practices and approaches to support the welfare, well‐being and development of children and young people.’

Calvert helpfully describes the timeline of growth and the form that pastoral care in UK schools have taken over the past five (now six) decades by dividing these stages up into the ‘seven ages of pastoral care’.

(1) Pastoral care as control - the growth of positions such as Pastoral Deputy, Head of Year, Form tutorial as a hierarchical structure that was bound up in notions of control and power.

(2) Pastoral care as individual need - a growing interest in counselling and the expectation that teachers would provide individual support lead to unevenness in the quality of provision, due to both a lack of willingness/ability/support to meet these needs and a divide between a more traditionalist (disciplinarian) and a more progressive child-centered approach.

(3) Pastoral care as group need - the shift towards trying to meet individual needs in group situations and giving individuals help but not delivered individually (i.e. form tutors).

(4) The pastoral curriculum - recognition that the pastoral curriculum should be a part of the whole-school curriculum and the inclusion of school-based activities that relate to personal and social development.

(5) Pastoral care post implementation of the National Curriculum - During the 1990s there was a growing preoccupation with the hierarchy of academic subjects and subject performance and assessment - Personal and Social Education became largely neglected.

(6) Pastoral care for learning - the early 2000s saw a return to pastoral provision as the dangers of a performance (over learning culture) was recognised, as well as the fact that emotional and psychological health and wellbeing contribute to academic achievement.

(7) Pastoral care, the wider workforce and the Every Child Matters agenda - the late 2000s the provision for schooling became more diverse with different types of schools and specialisms. Also a shift towards a greater dependence on ‘paraprofessionals’ which used to be the remit of teachers (support/mentoring/disciplinary roles). A shift back somewhat towards academic output with new definitions of pastoral roles (Learning mentors, learning coordinators, etc).

Whilst it is important to note that the aim of this article is to focus more specifically on international schools (and acknowledge my own bias towards discussing British Curriculum schools as that is my experience), it is interesting to see these developments in pastoral provision in the UK, as they undoubtedly, to differing degrees, have affected the form that pastoral provision has taken in some international schools.

These ‘seven ages of pastoral care’ are placed within the wider political context and the prevailing wisdom regarding education at different stages in time, and show in a more nuanced way (arguably) the cyclical relationship between education, teachers and wellbeing. The recent global pandemic may play a significant part in this new phase of pastoral provision which it seems to be coming back to a greater focus on wellbeing - and it is likely that teachers may be asked to once again play a role in this.

In wanting to wrap this article up in a semi-timely fashion I wanted to bring us back to Rosling’s notion that things can be both ‘bad and better’. In some ways it feels like things are shifting back to a more holistic approach in schools, partially because of the need arising from the current pandemic. I completely understand and appreciate the resistance towards teachers having to do more, and that it feels like teachers now have to be both academically-focused and make time to consider student well-being, with no concession in workload. More now than ever we should be looking out for our teachers, and for each other. However, despite this ‘bad’, the hope is that school is a ‘better’ place to be for students than ever before.

On a global scale, schools are now responding to the wellbeing needs of students and recognising the potentially negative impact of not doing so in both the short and long term. Wellbeing has always been at the heart of what teachers do (and do well) and regardless of their personal philosophy about their role, it is indisputable that they play an integral part of the social system of every young person they teach. The only difference appears to be whether wellbeing is positioned (politically at the national level and within schools) at the forefront or in the background of teacher priorities. The trick now is to find a way to ensure that teachers taking on more of a role in helping with wellbeing does not lead to burnout.

The dilemma here is even trickier with a public rhetoric of needing to get students to ‘catch up’ on academic content, and supporting their wellbeing, whilst not losing sight of your own as a teacher (sounds like juggling chainsaws).

Let’s hope that schools make this next shift part of the ‘better’ narrative.

Dr Sadie Hollins currently works as a Head of Sixth Form at an International School in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Prior to working in international education she worked as a HE lecturer and researcher focusing sociological issues in sport.

After a decision to take a different life path, she moved to Chiang Mai, where she has been based for the past four years. During this time she has had the opportunity to work in a residential rehab facility, and as a school counselor. She is passionate about the concept of change and creating inclusive and aware schools for students, staff and parents.

INTERESTED IN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION?

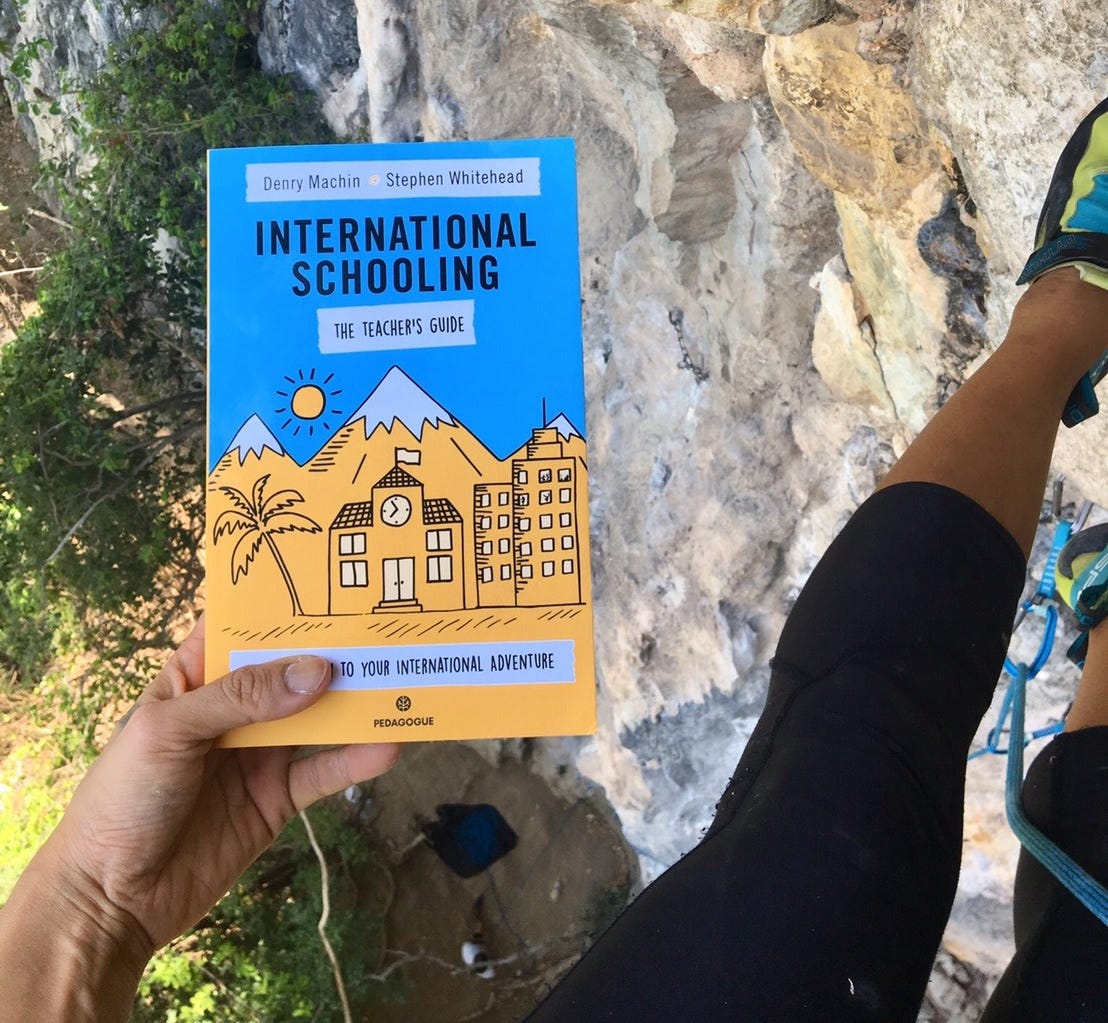

The Teacher’s Guide is getting around! Seen here up a cliff face in Thailand. When we said ‘a companion to your international adventure’ we didn’t quite mean literally!

Grab a copy to take on your own adventure.