Lesson Planning: Why it is better to be consistently ‘Good’ rather than ‘Outstanding'

The Long Read

By: Dr Mike Whalley

All of us in the teaching profession will have taught good and poor lessons. Those who claim they have never taught a bad lesson are delusional.

I suggest that ‘outstanding’ lessons, whilst fantastic an experience for the pupils concerned are unattainable on a regular basis and it is better for the pupils to receive consistently good lessons as a more sustainable and realistic level of provision.

My recollections and thoughts on good and poor lessons are based on thirty years teaching in secondary education in both independent and state schools. My thoughts are therefore based on the lessons I learnt from this educational sector. Those who teach in other sectors will no doubt have different experiences and subsequent thoughts on what makes a good lesson in those areas.

Nevertheless, there are parallels regardless of which sector the teacher works in and I hope that some principles of good practice can be shared as a result. No two lessons are ever the same, but we can try and make sure they are as good as we can make them, as often as possible.

Close your eyes and imagine…

The lesson has been meticulously planned, taking into consideration the needs of the targeted group of pupils. The activities and work requirements have been designed to be challenging, rewarding and appropriate to the differentiated needs of the pupils and in alignment with their targeted levels of progress. The lesson is one that is going to be ‘outstanding,’ but not a ‘flash in the pan.’

This lesson has been hard to prepare for, but it is perfect.

Data can be taken from this lesson and analysed for markers to inform further teaching and learning. All the equipment and resources are in place to augment the lesson plan. The objectives are clear, and the pupils are aware of how they fit into the programme of study they are experiencing. The children are respectful, work hard and enjoy their lessons. Yes, they will contribute in a lively way, but the noise will be a productive hum of activity.

You may intervene at points when the children are working independently, but this will be to challenge, offer alternative activities or consolidate the efforts already being made. The children might well be inspired by the lesson they receive today because they must trust you, believe in you and understand whatever you do, whenever you do it, is in their interest.

You are exhausted, up late and working through the weekends preparing this lesson, and others like it.

But that is ok, because the pupils will get so much out of it. The Head and management will appreciate your efforts and see the magnificent work you are doing with this class. The preparation for this lesson is on top of the massive amounts of reports, assessments, plans, inspection preparation, extra-curricular commitments and marking that you already do, but its going to be worth it.

Here is a more likely scenario.

The time for the lesson arrives. This is just another school day like any other, nothing to stop this forthcoming lesson be ‘outstanding’ if an OFSTED body was watching. Five minutes to go and you are in the classroom ready to go. But wait, the Head walks past and wants to talk to you about something “pressing” that takes your mind of the lesson in hand.

The pupils arrive and they are obviously pre-occupied with something. What has just happened? A petty argument between two of the pupils over something very trivial to you but a major catastrophe to them. It takes time for you to settle the class and there is something not right about the atmosphere in the room.

Then child A tells you they have forgotten their books or equipment. No problem, you have experienced this hundreds of times before, but then Child B also tells you that they have forgotten their books. Child C asks to go to the toilet (although they have just had break), Child D and E are still arguing. Child F is late as he is the reason for the discussion with the HM before the lesson. The heat of irritation is beginning to run down the back of your neck.

Finally, the lesson starts.

You introduce the topic, but the pupils seem disinterested. One mutters that this is boring whilst another suggests it is too easy. Another asks to go to the toilet. You struggle through the teaching but its not working. The children are actively disengaged and anything but the task in hand is more interesting than your lesson.

A low flying helicopter outside really helps the situation.

Your get-out is the opportunity to watch something via a media presentation but the internet will not load up. Trying to locate IT support now will require the manhunting skills of a private detective. An attempt to return to paper resources is met with actual revulsion at this point. By now you have lost your patience with everything and everybody. You think about changing the theme of the lesson, but why should you? Its up to the pupils to show some respect and listen and pay attention. You lose your temper and the ensuing silence after your Churchillian speech about respect for someone else’s efforts gives you a chance for you to get back on track. You decide that the pupils should do some quiet, related work so that you can regroup. You feel back in control, but the lesson is hardly inspirational now. Any attempts to drum up support now will just look like you are being soft, so you decide to remain strictly in control mode.

This is in a ‘good’ school.

It might be that we do not get beyond the starting post in a lesson because of issues surrounding behaviour, disrupted routines, poorly organised pupils, punctuality, and a whole host of reasons why lessons will be far short of outstanding in most schools. For many, the likelihood of a reasonable lesson will be very unlikely before the start of the lesson.

But, the long hours of preparation, marking and planning continue, and the lessons will come around again. Daily, weekly, termly, yearly. The different possible influences on teaching and learning in lessons throughout these periods is staggering. Schools are not factories where we press buttons and churn out manufactured academically capable, socialised, emotionally stable young adults ready for the next stage of education or the workforce. Each minute of the day in a school is different and it is impossible to plan for every contingency, good or bad.

As teachers, we have all been through both lesson scenarios.

When all goes well, you feel like you are the best teacher in the world, but when it all goes wrong, you are looking at the LinkedIn jobs at 7.00 pm that night. When you have spent all that time preparing lessons that you think will have a real impact on pupils and they work, it is a massive boost to your confidence and motivation to continuing going beyond for the school. When it goes wrong you ask why bother?

There is often no rhyme or reason a lesson works well in one situation and fails in another. There is no formula for an ‘outstanding’ lesson, but it is true that consistently good teaching results in good learning. OFSTED repeatedly states correctly that there are many routes to excellence, so what makes one lesson outstanding might not be for another, what works for one teacher might not work for another, what works for one class might not work for another and what works in one school might not work in another. If ‘outstanding’ is so hard to identify amidst so many variables, surely it is better to concentrate on what we can control, and be better more consistently across a wider section of educational provision rather than chase the unattainable?

These statements on variables are so true.

I can recall many situations throughout my career where I have had a good lesson with one group, but it has failed miserably with another. I have passed on lesson ideas to colleagues who have found them to be a complete failure with their groups. I have pinched ideas from friends and colleagues that have worked well for them but then fail miserably for me. And all the opposites of the above statements are true. From experience I can confirm that a lesson with a group in an Independent School is not likely to work with a group of pupils from a secondary school in a socially and poor area, and vice versa.

But we can analyse some of the variables that can be in classes because they are the key influences on whether a lesson will be a success or failure. For example, the planning (or poor planning) of a lesson is an effective way to start this analysis.

Planning

Preparation is one of the key aspects of great lessons, but it must only be part of the wider medium- and long-term planning of the teacher, department, and school. Therefore, the long-term plans must set the foundations for great lessons by setting out the intentions for pupils’ development and progression. A good lesson that contrasts with a poor long-term plan is just a one-off exception to a banal programme. A poor lesson in contrast to a good longer-term plan fails to match the grand expectations and standards set on a wider scale.

Planning a great all whistles and bells presentation and series of learning activities can not be done every lesson. If it takes longer to prepare the lesson than the lesson itself, you will be doing more work out of school hours than in them. In an ideal world, all lessons will be perfect as described above, but as reality kicks in, you must face facts and accept that your aim should be that all lessons are consistently of such a standard that targets are met in terms of pupil learning and progress, engagement, contribution, challenge, and reward. In fact, pupils will make more progress over a longer period having good, consistent lessons rather than the occasional one-offs amidst some mundane and unchallenging lessons.

There is such a lot that can be done in preparation for a series of lessons that will always contribute to successful lessons. As discussed, the lessons should be only part of a wider ambition for the pupils, but a teacher can have a more detailed idea of where this series of lessons will take each individual pupil. The planning of detailed lessons is essential, must be progressive, and challenging. Good lessons differentiate pupils naturally, poor lessons do not. Evidence of the progress of the pupils will be able to be seen because of these lessons. One-off lessons will not likely capture the medium-term progress that a series of good lessons will gather.

Planning a series of good lessons will need the organisation of resources and activities that can be prepared well in advance. If they are ready, any upsets in the actual lesson might be avoided. Valuable resources can be used again. Build up a bank of resources that can be used in a range of lessons. Some resources can be turned to as absolute bankers when in need of something at short notice (when a lesson is going badly!) or to consolidate work done in class.

Too often, lesson plans are too ambitious and there is no way that the pupils will be able to cope, or there will be enough time, for the objectives to be met. Teach one thing at a time properly rather than numerous things poorly is a sensible measure to implement.

We have all seen lessons where a seasoned teacher arrives with no books or equipment, uses the minimum of resources yet still produces the most fantastic lessons. This is all experience. The teacher in question will undoubtedly have taught the same type of lessons hundreds of times, with variations to suit the unique characteristics of a particular class or group. This teacher will have taught bad lessons but will have learnt from the experience and has moved on using a better plan next time. However, the better teachers, in my experience, are always looking for innovative ideas and contemporary techniques that help them shape their already present good practice.

Disruptions

Away from planning there are many solutions for the irritating disruptions a teacher encounters daily.

Things like pupils forgetting books, equipment, and homework, are nowadays resolved by keeping work/class books in school, having enough spare equipment and use a variety of IT systems and resources so that pupils can do work and homework using technology that can be saved and sent to you (and therefore not lost).

Obviously, care must be taken with privacy and data protection here, but there are so many ways around the use resources for capturing pupils work there is no excuse these days for lost or forgotten work. I am sure my colleagues in a wide range of schools will have thousands of different techniques to alleviate this problem.

On the topic of external disruptions, this is a school issue. The school ethos should not allow disruptions to lessons. Teachers should not normally be interrupted unless it is vital. The school environment should be business-like and classroom environments should be sacrosanct as places of study and learning. Having said that, I have worked in schools where it was considered appropriate for visitors to be shown around and look in on classrooms and talk to teachers. A mixture of both is most realistic, where classrooms should not be disturbed, but pupils should expect visitors and welcome them when the situation arises. Overall, disruptions should not be a deciding factor on whether a lesson should be a success or not.

Behaviour

The behaviour of pupils is also a school matter.

It should be a priority for the governance all the way through the school to classroom practitioners. If pupils are badly behaved in your lessons, they will be in others. The school approach to pupil behaviour should result in them arriving at your lesson ready to learn. Low level disruptive behaviour is disastrous to the delivery of a lesson however well planned and it should be a school priority to tackle this type of behaviour to support all teachers.

However, you can set the tone for all your lessons by setting clear expectations early on, and consistently applying those expectations often regardless of whatever else is going on in school. This can be done at departmental level to add a specific range of expectations particular to your subject. I worked in PE and Games for the best part of my career and establishing rules and regulations for this practical subject was crucial. It is also here that you should discuss and formulate what makes a good lesson for this subject.

Not all pupils are poorly behaved.

In fact, most pupils (and their parents) want schools to be a place of learning and opportunity. It is an awful shame when the education of such motivated children is hindered by low-level disruption in a lot of their classes. Sometimes a well-planned, organised, and disciplined lesson is an oasis for many pupils who want to learn and make progress. Poor behaviour should be the exception, not the norm in classrooms.

Communication

As the teacher, you are the most valuable resource for that lesson. The sponge in the trifle.

This is a fact often ignored by those criticising already overloaded teachers doing their best to manage the workload. You can have the best prepared lesson in the world, with accompanying resources, but if you cannot communicate the aims and objectives of the lesson to the pupils all that preparation will be wasted.

I have known the most conscientious teachers wonder why their fantastically prepared lessons are met with indifference and poor engagement by the pupils who quite often become bored quite quickly and disrupt the lesson. The problem here is not the lesson, although some clearly did not match the needs of the class or the pupil, it is the lack of communication that is clear. Communication in all its forms from verbal, body language, identifying signs of engagement by the pupils, listening skills, and written instructions provide that vital link between the planned lesson and delivery. I am afraid to say that communication skills are so important that if you have not got them, do not teach.

Consistency

Good teachers are consistent.

They are subject experts and can communicate to classes and individuals alike. Pupils like consistency, black and white rules, and surprisingly routine. To be a performance artiste one lesson and then Mr Chips in another will only leave the pupils confused and wary. Whilst a variety of teaching styles and techniques is necessary to keep the pupils attentive, a degree of consistency is equally important.

So, remain level-headed and moderate in all your actions and behaviours so the pupils know exactly what they have got when they are in your lesson.

So, we have the perfect lesson (which does not exist) and some of the reasons why they go wrong. I have tried to discuss how some variables can be managed. Good lessons are well prepared and are well resourced. The teachers can deliver this lesson because the school is a place where learning is prioritised and pupils are aware of their obligation to behave, listen, work hard, show respect, be well prepared, engage and contribute to the learning process. All the above can be achieved with a collaborative effort from all stakeholders involved. The excellent lessons are rare though, but the best teachers can adapt to the ever-changing scenario in front of them.

For those of a certain persuasion, a review of official literature, guidelines, and recommendations on what is a an ‘outstanding’ lesson will reveal that there tends to be an agreement that certain positive characteristics and variables are present in the preparation and delivery of such classes. I am pleased that many of the variables I have identified are included in such discussions. Just as there is no perfect Orwellian “The Moon is Under the Water” pub, they will also agree that each teacher, school, class, pupil is different, and it is too difficult to formulate the perfect lesson amidst so many variables.

The perfect lesson is therefore impossible to identify.

I would agree and say that as there are too many variables to generalise, lessons must be borne out of established good practice in each school where the unique characteristics have a crucial impact on any long- or short-term planning. My advice is to share such good practice in your school. If a lesson works, share with others. Seek help and advice from those who have impact in lessons as well as learning from mistakes, making the positive aspects of the variables discussed more consistent and the negative less frequent. Find out what works for the pupils in your school and provide good lessons consistently. ‘Outstanding’ lessons are fantastic, but can we realistically plan for these for all of the thousands of lessons that we might teach in our careers? We simply do not have the time or energy to do this.

Whilst burnout is proving to be the key factor in teacher recruitment and retention, we must prepare our work in a realistic and sustainable fashion that keeps us healthy whilst maintaining a consistently high standard in teaching and learning.

By: Dr Mike Whalley

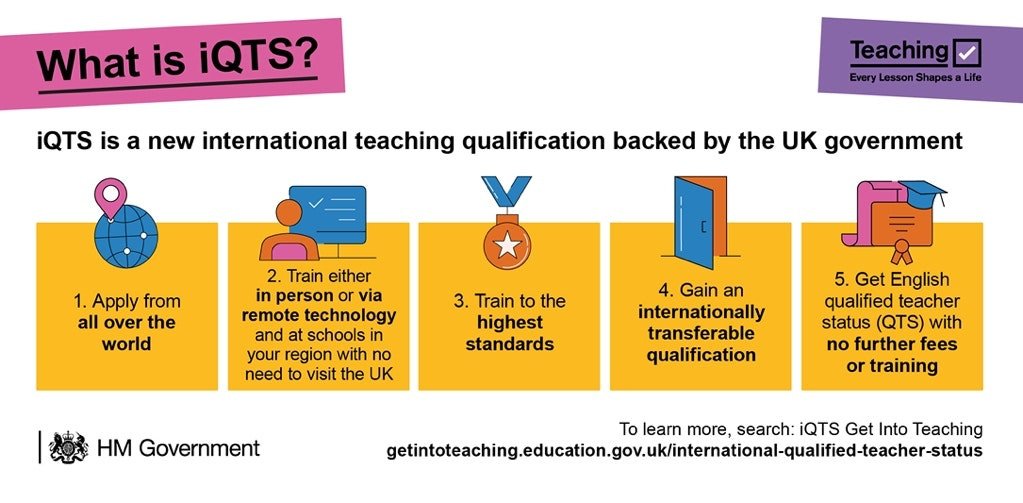

The New PGCE…now with added iQTS

As you've no doubt read, the UK Government is piloting a new PGCE iQTS programme, recognised by the Department for Education as equivalent to English qualified teacher status (QTS).

The University of Warwick is delighted to be one of a select few providers offering this exciting new programme for August 2022.

As you’d expect, the course is rigorous and robust. For an overview of the requirements, there is an outline (and individual eligibility checker) HERE.

The introduction of PGCE iQTS also means a few changes for Warwick's highly successful PGCEi programme. The admissions and placement criteria have been simplified; head HERE for further information.

A useful comparison of the PGCE iQTS and PGCEi courses can be downloaded HERE.

If you have staff interested in either programme, please feel free to share EDDi.

Or, alternatively, questions can be e-mailed to: pedagogue@warwick.ac.uk