‘Crafting ? Gender and Identities in Senior Appointments in Irish Education

D. Devine, K. Lynch and B. Grummell

There is a letter missing in the word ‘Leadership’.

The letter C.

For you it might stand for confidence. For other leaders it might stand for control. A third option would be conflict.

For me, it stands for compromise.

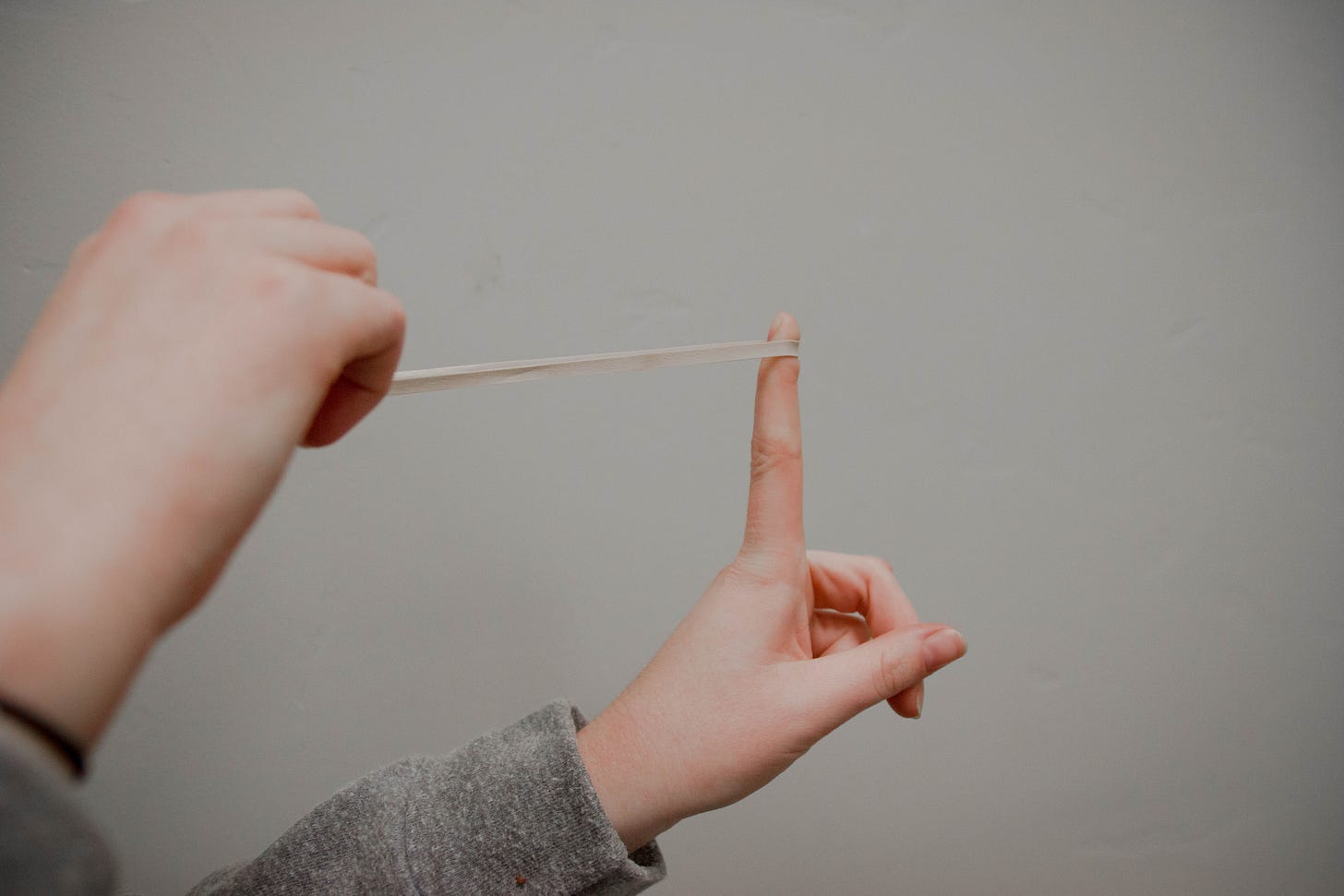

Leadership is nothing if not an exercise in self-management, in the ability and willingness to compromise and know when and when not to do so. Those leaders who cannot bend will eventually break. But bend too much and you will end up with no discernible identity whatsoever. Nor will you have much authority left.

Another way of describing it as ‘elasticity’ – the ability and willingness to shift one’s shape to suit the dynamics of the situation, the characters of the people you are dealing with, the pressures of the organisational aims, climate and culture, but without losing sight of your overall objectives.

Maintaining some sense of an ‘authentic self’ in all this is quite a challenge.

But then, perhaps the very notion of an authentic self is the problem. We are all work in progress, not predetermined and fixed identities.

These pressures are present for all leaders, regardless of their particular identity mix. But as this article explains, women leaders, confronted by the ‘culture of new managerialism’ present in education especially, must become adept at developing this ‘elastic self’.

“…we highlight how the culture of new managerialism leads to the crafting of an ‘elastic self’ among senior managers in Irish education. This requires a relentless pursuit of working goals without boundaries in time, space energy or emotion. We explore how the experience of this elastic self is gendered, deriving from the moral imperative of women to be primary carers, as well as the need for both men and women to manage ‘otherness’ and ‘do’ or ‘undo’ their gendered identities in line with organisational norms.” (p. 2)

As I have written elsewhere (Whitehead, 2001), management and leadership offer potent sites for identity investment, traditionally for men but also now for women. However, to imagine that women and men experience leadership in precisely the same ways is to misunderstand what it means to live as a man and to live as a woman. Gender is a social construct but that doesn’t make it any less influential on the lives and subjectivities of the individual. And once women enter the traditionally masculinist realm of management and leadership so they are subjected to a very different scrutiny than that experienced by men/males.

All this was true long before a further element entered the world of (education) management one which was to make these pressures even more intense – performativity.

“Performativity is the trend in organisations to measure and quantify every aspect of employee performance (e.g. targets, assessment, performance indicators, appraisal, success measurements)’. (Hollins and Whitehead, forthcoming).

“For women in highly performative work environments, being elastic not only involves meeting the requirements of organizational productivity (and as with men) the fashioning of the self as the 24/7 worker, but also extends to doing caring work both within and without the organization in feminine-defined ways.” (p. 6)

As the authors note, Irish governments have followed the global trend towards neo-liberalism in education, the introduction of a ‘market-driven model of efficiency and accountability’ all reinforced by a system which polices and appraises the individual as a resource of production against given targets.

While politicians and policy-makers may see all this as a ‘good thing’, an almost reflex reaction to the dominance of global free-market capitalism, the reality is it impacts directly on people’s identities, and on the gender binary.

Especially in school leaders(hip):

“As key negotiators of organisational culture senior managers are compelled to negotiate their identities in the context of such change, engaging in a modality of control that includes ‘managing the insides’ (Alvesson and Willmott, 2002:3). Flexibility, adaptability, self empowerment and self actualisation are incorporated into the new worker identity (Halford and Leonard 2001). The experience of management in this changing context can be a double- edged sword. On the one hand, there is a seductive aspect to management as a site for identity investment through the promise of power, status and purposeful action (Whitehead, 2001). On the other hand, deep insecurities arise, deriving from increasing surveillance, performance and accountability demands (Collinson 2003, Linstead and Thomas 2002). (p. 3)

The Research

The article draws on studies of 23 top-level educational appointments in primary, secondary and higher education across Irish education – eight primary schools, eight secondary schools and seven HE organisation. The research aimed to ‘identify the cultural codes enshrined in both the process and experience of the appointment as well as the appointees experience in post.’

The methodology was qualitative with (45) in-depth interviews not only with the appointees but also senior managers with considerable experience of management within the education system. There was an equal gender balance of interviews within the school-based research.

Summary of the Findings

1. For senior women ‘doing’ gender also requires coping with feelings of isolation/loneliness on a male dominated SMT.

2. Senior women leaders are coerced into a ‘double binary’ in terms of managing what it means to be ‘female’, ‘boss’, ‘manager’ and ‘friend. All this acts as a potential deterrent to them applying for promotion.

3. Younger women in SMT struggle to be taken seriously due to the ‘looked-at-ness’ of the feminine identity.

4. All senior managers, regardless of gender, are ‘stretched personally and professionally’. They have to appear as ‘super-leaders’ and expected to ‘maximise the investment of self’ in their work identity.

5. Being in SMT demands ‘a relentless commitment to the strategic goals of the organisation and carries an implicit assumption of 24/7 availability’.

6. In senior management, individuals had to both ‘do’ and ‘undo’ their gender identities. For women leaders, this requires combining ‘caring work’ with their SMT demands. This stretching of self is not generally evident with the male leaders.

7. Masculinised organisational cultures are evident as one moves through the education sectors, even in the more feminised primary sector.

8. The ‘ideal’ leader is visualised as one unencumbered by care responsibilities outside the organisation even while women leaders are co-opted into caring roles within the organisation.

9. Men leaders in the study who had care responsibilities did not have to engage in the same degree of emotional labour in managing the time-bind between work and home as did women leaders.

10. Gender identity is practised at work for both men and women but operates within the context of the masculinisation of management and a culture of masculinism.

11. The above patterns appear to becoming more, rather than less embedded under neoliberal management reforms in education.

Finally, the authors point out that the above pressures are not simply resolved by ‘adherance to strict legislative criteria for gender equality’ because this masks the deeply rooted forms of exclusion, marginalisation, gendering within management and leadership.

In other words, the elasticity of self, and the way this stretching of identity to meet various demands is required of all educational leaders, is not ameliorated simply by following best practice in terms of equality, diversity and inclusivity.

What needs to first be named and challenged is the organisational culture of performativity because this now carries powerful gendered expectations of leadership across education.

Article summary by Dr Stephen Whitehead

reference

Devine, D., Grummell, B. and Lynch, K. (2011), Crafting the Elastic Self? Gender and Identities in Senior Appointments in Irish Education. Gender, Work & Organization, 18: 631-649

link

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00513.x