The Trials and Tribulations of Postgraduate Study While Also Being a Teacher: A Reflective Trilogy

Part Two: The EdD Experience

By: Dr Mike Whalley

This is a series of three short articles on my experience of studying for a Professional Doctorate in Education (EdD) whilst in full time employment as a teacher in a UK independent school. What I present is a collection of thoughts, emotions, and memories from the experience, beginning with the decision to embark on such a difficult journey, the practicalities of studying at such an advanced level whilst in full time work, and the surprisingly mixed emotions on completion. I hope these thoughts might serve as advice and guidance for fellow educationalists considering the PG journey.

In part one of this trilogy about my experience of postgraduate study whilst in full time employment I recalled the process of deciding to embark on this adventure.

In this second part I describe key parts of the five-year study.

The Beginning

I began the taught modules of the EdD in November 2006.

Luckily, I seem to remember that all these modules were delivered during school holidays. I would not have chosen this course if the taught sessions were in school time, as to take time off would have been impossible.

Having not studied since the completion of an M.Ed. in 1998, I was nervous at the prospect of returning to academic study at this level, and experienced real imposter syndrome on my arrival for the first meetings. However, having met some new study colleagues and staff, I soon realised that all the cohort were in the same position, and I had nothing to worry about.

The first taught modules were academically demanding, and I asked myself whether I was up to it. Of course, I had made the financial and psychological commitment to study, so in this respect there was no going back.

The first module introduced the various theories and methods used as an educational researcher, followed by an assignment to author a personal research biography, an early reflexive examination of my subjective relation to my experiences in education.

Other modules also introduced us to different sociological theories and the key contributors to such research and current educational debates. I learnt that educational theory, policy, and practice are interwoven and as we progressed the need to engage theory with my own research interests became clear.

Why an EdD rather than a PhD?

Although the two doctorates hold equal status in terms of academic standard, there are crucial differences in the course content, teaching style and purpose.

Whilst the PhD is achieved through independent research (with obvious supervision and assistance), the EdD is aimed at experienced professionals who want to seek solutions to educational problems and contribute to decision and policy making processes at work through reflection in conjunction with reference to contemporary research.

This was the appeal for me.

The EdD was a means to analyse, in fine academic detail, the relationship between educational structure and policy on the one hand, with the experiences of teachers at the sharp end of the profession on the other.

I had this clear in my mind as I made progress through the taught elements.

The Taught Elements

The taught modules progressed on the theoretical components of research and assignments were geared towards us designing a research method from a particular theoretical and epistemological perspective.

It is now a year since I commenced the course, and I was doing some heavy academic research into such research methodology underpinned by a particular sociological perspective.

Five months later I had to prepare a thesis proposal which then had to be presented to a Thesis Proposal Conference. This was a daunting task, presenting my ideas to the other students and staff at the university but I was delighted when my proposal was passed a fleeting time later.

It is important to outline my theoretical stance as it directed the course of my research and final dissertation. Others who are contemplating taking a EdD will go through this process of adopting a perspective to shape their research.

As stated in the first section of this exercise, I was interested in the concept of ‘performativity’ in education.

I found this concept located through postmodern analysis. Connected poststructuralist analyses emergent knowledges, productive power and normalising regulatory systems of performativity as a dominant discourse within which provide how subjects are confirmed as individuals, through projects of gendered (in this case masculine) identity, subjective power, and resistance.

This directed me to embark on a subjective, reflexive exercise to investigate a personal, professional relationship between performativity, management practice and masculine discourse.

The Thesis

For my thesis I decided to interview a sample of teachers who had an extended managerial relationship with performativity.

This would collect qualitative data.

I conducted a pilot exercise a year before the research project. This was a time consuming but necessary part of the process and valuable lessons in technique and protocol were learnt from interviews with a small number of volunteer colleagues.

Then, for the actual project, in-depth interviews with twelve managers using semi-structured questions were used to discuss how managers lived out an experience within performative discourse. I gave the participants some information about the research project prior to their interview.

Despite the theoretical complexity of notions of performativity as a dominant discourse and the gendered subjective ‘self’ I felt the participants could talk openly about their teaching lives.

The Research Questions

The research questions were crucial to the whole exercise. They provided the bridge between theory and experience.

They were centred around the key themes of performativity, masculine subjectivity, and professional ontological security. However, the research questions are not the interview questions; they provide the theoretical foundations on which the actual interview questions can be constructed.

The evidence gathered from the interviews then is set against the original hypothesis for evaluation and further discussion. If the research and subsequent interview questions are correct, they set the agenda for progress in the study, but they should not simply confirm the hypothesis, they should direct to further discussions and argument and suggest possibilities for further enquiry.

Yes, it is satisfying to have a full or partial confirmation of one’s ideas, but alternative, even opposite suggestions that prompt wider consideration (and further time-consuming research) must be anticipated and even welcomed.

I liken the construction of the research questions and the ensuing interview questions to the work of a detective in a criminal case.

In trying to solve a crime, the detective and his/her team will have gathered evidence that must be tested. They have their suspicions about what has happened and who might be responsible. They have their suspects who they consider responsible under arrest and must be questioned. During interview, the detectives must ask the correct questions to confirm that their version of events, place evidence correctly at the scene and identify the role of the suspect in the crime. The right questions will confirm the truthful series of events and confirm that the correct evidence has been collected and fits accordingly. The wrong questions will not assess the evidence, the detective’s suspicions about what happened will be cloudy and will cast doubt over the role and involvement of the suspects. The case, with its investigation lacking in accuracy and consistency will collapse under forensic scrutiny by an expert defence lawyer.

Yes, I have been watching and reading too many criminal investigation stories, but the parallels are obvious.

Failure to have a complete picture of your research field and then ask the correct questions will lead to poor, inconsistent, and debatable conclusions drawn from the collected data which will be scrutinised, questioned and even dismissed by expert witnesses!

I was confident that I had prepared the research questions thoroughly and anticipated the possible journeys that each interview might travel. I was therefore pleased and relieved when many interviewees took the opportunity (once confidentiality and anonymity had been confirmed) to express their honest feelings about their working lives amidst performative regimes ranging from frustration, anger, anxiety and disappointment to satisfaction, pleasure, and promise.

The Interviews

The interviews were tape recorded, transcribed, coded, and then analysed in a manner that would stimulate discussion surrounding themes and issues relating to the research questions.

The analysis of the date was complicated, highly technical, and very time consuming, but produced fantastic information that could then make a vital contribution to the thesis.

The aim was to see how the teacher-managers experiences related to my own experience and to the findings of my deep academic research.

It is interesting to discuss how the results of the interviews in relation to the research questions either confirmed or challenged my prior thoughts, experiences, and expectations. In many respects the responses confirmed my expectations, but there were some interesting alternative observations that added a great deal to later discussions.

For example, the teachers reported that managerial behaviour, roles, and strategies had been strongly influenced by the market-driven forces and regulatory mechanisms of performative discourse. They also partially confirmed that an ‘assumed’ type of masculinity, one characterised by purposeful rationality, instrumentality, and control was linked with a new professionalism providing the opportunity for ontological security. This is expected, but many also argued that there were too many variables in performative managerial cultures to confirm a privileged masculine code of behaviour and practice and managers could also switch between newer versions of professionalism influenced by performativity in a rational, controlled, often aggressive manner in one situation, and then be much more collaborative, cooperative, and emotive, in another.

Thus, a fragmented manager-subject can be identified, with multiple identities capable of a wider range of tactics and strategies emergent in response to the multiplicity and fluidity demanded in such structures.

Also, many managers spoke of their experience of fabricated responses and inauthentic presentations of self; a plurality required to complete performative tasks. These were ‘appropriate’ responses to certain situations necessary to ‘play out’ roles to achieve a satisfactory conclusion and no doubt ease ontological anxiety in these stressful environments; an array of responses displayed by colleagues that I had witnessed all to often.

The Draft

Drafting the thesis was also an exceedingly difficult and a lengthy process.

The first chapters of the thesis introduced the key theoretical concepts of the thesis with a deep review of literature. This included chapters on performativity, the centrality of education under contemporary market reform and locating the masculine subject.

These chapters were written before the interviews.

I always felt I could write well. However, in my attempt to cover every aspect of a discussion or argument I tended to write too much. It was better to remove rather than find but this was a time-consuming process.

I was also poor at maintaining a bibliography and reference system throughout writing up the thesis.

This laziness was to cost me dear later. I had to spend hours chasing up references and updating a bibliography to make sure I acknowledged the work of others.

This is such an important part of the writing process but equally forgotten.

I hired a proof-reader to go through my work. This was expensive, but crucial to the production of the final dissertation.

I was lucky to have an incredibly supportive supervisor (thanks Stephen!) who assisted me as I drafted the dissertation, reviewing, advising, and suggesting alterations as I progressed chapter by chapter.

You need this continuous support. Left alone you can easily go astray which can be difficult to return from.

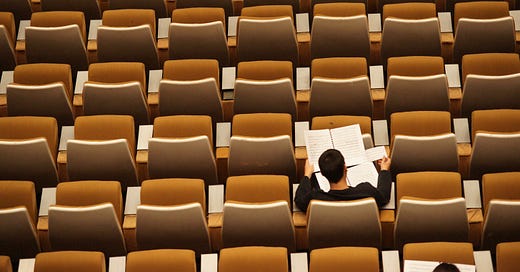

Writing at this level is a very solitary experience. I was able to meet my supervisor in person periodically or via skype. Online communication is even easier now than it was in 2010/11 so constant contact with a supervisor without the travel implications I often encountered should not be a problem.

You need all the resources required for doctoral study readily accessible. You need access to the library at your research institution or access to another nearer to you if you live a long way away. I was able to register at my local university as an associate member. I was therefore able to use and borrow their resources. It is also vital that you have access to the vast array of online resources available through your host institution.

The thesis was submitted in May 2011.

The Viva

I knew I was due to have to go through a thesis defence but when the notice came informing me of my date later in September, I became nervous.

It is awfully hard to prepare for the defence.

It is one thing to be able to write and discuss your work with your supervisor, but I knew I would find it difficult to articulate to this new audience.

The only advice I can give is that you must know your research in the finest detail. You must be able to defend your ideas and process, but also acknowledge that there might be flaws and counter arguments to your thoughts. It is natural to believe your thesis is infallible, but this is not the case, and you must be ready for criticism and alternative points of view.

I made copious notes to accompany me at the defence, with post-it notes in parts of my document marking areas in which I might be asked to discuss theory and research, but I am not sure they were of any use. I found the internal examiner supportive and the external more questioning and critical. I must have done ok though as after I was asked to leave, a little later I was told to return to the room to be told that the thesis was to be passed with minor alterations, the outcome for which I had hoped. I dreaded a verdict of major changes or rewrite.

I am not sure how I would have coped with such news.

Once the viva had been completed, with minor alterations, and again proofread, I was desperate to submit so that I could graduate by Christmas.

I remember the day the dissertation was printed, bound, and sent back to me (again expensive) ready for submission to the library at Keele. This was a proud moment, but wait, there was a misspelling of my name on the front cover! A panicked call to the publisher, waiting frantically for its correction and return a day later and then a mad rush down the motorway after school at 4pm to Keele before the 5pm deadline was not the easiest of days.

Following this harrowing experience I needed closure, and a rest.

To prolong the journey beyond Christmas would have been exceedingly difficult for me and my family. Having said this, I completed the course in five years… a year less than the normal length of time recommended for study.

And relax.

But what next?

What was the point of all this endeavour and sacrifice over the past five years? Was it all worth it?

Let us see what the impact of being a ‘doctor’ had on my professional and personal existence in the final part of this trilogy.

Subscribe to ensure Part III arrives in your Inbox.

Bio

Mike was a teacher for thirty years. He taught Physical Education in both state and independent schools in the North West of England becoming a Director of Sport, but also held roles as Pastoral Leader and Head of Boarding. He maintained his academic interests in education throughout his career, completing a Masters Degree in 1998 and a Professional Doctorate in 2011.

Mike retired from full time teaching in 2016 due to ill health and now works part-time tutoring Maths and English to children in alternative school provision.

INTERESTED IN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION?

The Teacher’s Guide is getting around!

Seen here in Thailand with a happy reader - and his new best friend. When we said ‘a companion to your international adventure’ we didn’t quite mean that kind of companion!

Grab a copy to take on your own adventure or listen to a short sample here (4 mins).