Which management practices are common in International Schools?

Alongside growth in their number, over the last decade international schools have experienced rapid change. The days of the amateur are…

School leadership…it demands a broad skill set

Alongside growth in their number, over the last decade international schools have experienced rapid change. The days of the amateur are fading. The industry is now increasingly corporatised, professionalised and bureaucratised. Good enough is, well, no longer good enough. To survive and thrive in this increasingly competitive space, schools must seek continual improvement. As a result, practices that used to mark out the few are now adopted by the many.

So, what are these practices? What tools and systems are schools adopting in order to improve and professionalise their practice?

With a focus on management, these questions formed the basis of a questionnaire sent to 150 international schools. The interest wasn’t in educational practice, that being covered in depth and authority elsewhere. Rather, the focus was tools and techniques, practices and procedures, used in management — human resources, performance management, target-setting, teacher contracts and such like.

A summary of the results is presented below. As not all schools answered all questions, the number of respondents is given (n=) for each data set. Where it offers insight, the data is also broken down into school-type (comparing not-for-profit, for-profit and corporately owned schools).

Teacher Contracts, Tenure and Turnover

As Chart I shows, two-year, and to a lesser extent one-year, teacher contracts seem to be the norm (with no statistically significant difference reported between school ownership types).

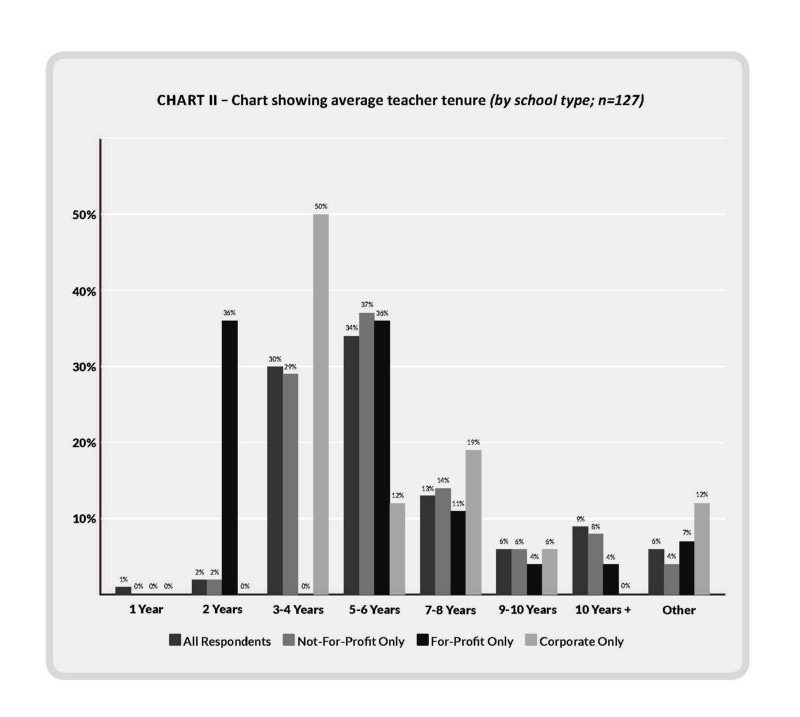

Chart II considers average tenure:

Of particular interest, average contract lengths appear to be shorter than average tenure; with mean tenures of 3–6 years spanning two or three contract terms.

This, of course, begs the question why schools don’t offer longer initial contracts or longer contracts on renewal. The answer, perhaps contentiously, is that shorter contracts affirm management power. Underperforming staff are more easily removed where contract terms are shorter; moreover, the biennial or, in some cases, annual, threat of non-renewal helps to keep the rank-and-file in line. That said, when committing to a new school (often in a new country) many teachers also favour shorter contracts; some being reluctant to sign for extended periods, even if longer contracts are offered. On balance, both the demand- (schools need for teachers) and supply-side (teachers desire for contractual flexibility) of the recruitment market appear to favour shorter (two-year) fixed-term contracts.

A further line of enquiry involved teacher turnover:

Not only is there limited difference between turnover in any one type of school, in general, there is also no significant difference between these figures and values of 14.3% for US teachers and 18% in the UK. With a sample mean of 11%, international schools are well in line with (indeed, better than) these norms.

Of course, in comparison with UK and US schools, it may be that international schools simply represent the lesser of two evils. If the alternative to working internationally is a return to the (potentially more challenging) environment of a teacher’s home country, then perhaps it is simply the case of ‘better the devil you know’; teachers stay in international schools because the alternative is no more appealing. It helps too, of course, that many international schools are located in countries that enjoy far better weather and far better standards of living than many teacher’s home nations!

Appraisal/Performance Management

Performance management, it seems, is part of international school life. Regardless of ownership type, responses indicated that the majority of sampled schools (86%) have some form of performance management system. Only in a very small number of the sampled schools (14%) are teachers free from performance audit:

To further unpick the nature of performance-management systems, the questionnaire asked what types of criteria staff were judged against:

Overall, 65% of Heads claimed to be accountable to student roll targets and 54% against financial targets; in contrast, a smaller proportion claimed to be appraised against general educational targets (26%), professional development targets (24%) and even examination results (34%). Commercially-inclined performance management does not yet seem to extend to teachers; few schools seem to appraise teachers against roll targets, for example. However, the evidence does suggest a leaning towards commercialism, so far as Heads (and to a lesser extent Senior Managers) are concerned.

Participants were also asked to indicate whether a system of ‘forced ranking’ was used. Colloquially known as ‘rank and yank’, forced ranking is common in commercial-sector organisations. Perhaps offering some solace to educationalists, international schools do not seem to have (yet) adopted this contentious practice; 65% of participants (n=109) indicated that forced ranking was not used, with a further 29% indicating that they were not even aware of the practice. In total, only 6 respondents claimed to use forced ranking (3 for-profits and 3 not-for-profits).

Performance Related Pay

Mindful of various attempts by Governments to introduce performance-related pay (PRP) in national contexts, respondents were asked to indicate whether PRP is used in their context:

Whilst the differentials are minimal (and within the margin of error so not statistically significant), interesting within this data is that slightly more not-for-profit schools use PRP than do other forms of school ownership. Also notable is that the proportion of corporately-owned schools offering PRP was lower than for other types of ownership. Those observations aside, it is clear that PRP is not widely used in the sampled schools.

The questionnaire also asked whether a quota system was used with regard to the number/proportion of staff on certain pay grades. Overwhelmingly, the response was “no” (90%). Only 9 schools (10%) claimed to use a quota system, 6 not-for-profits, 2 corporate schools and 1 for-profit.

Profit Share

In the case of the for-profit and corporately owned schools, participants were asked to indicate whether any grades of staff were offered profit share:

As the data shows, profit-share is not yet widely adopted in the sampled schools. A small number of Heads (17) enjoy (if enjoy is the right term) profit-share, but they are in the minority and a number of these indicated in their comments that they were the founders of the school and shareholders in the company, and thus, not on employee profit-share per se.

Performance Metrics

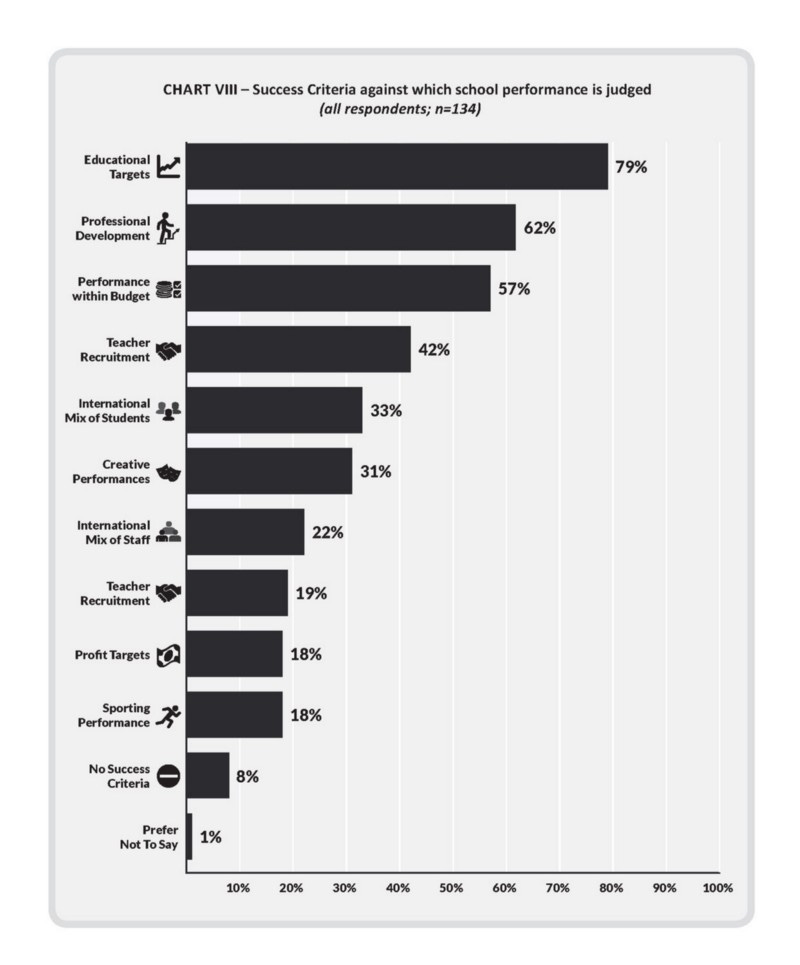

Shifting focus, participants were asked against what performance criteria their school is assessed:

Only 8% of respondents indicated that ‘no success criteria’ were used in their context. Unsurprisingly, nearly 80% of the sample claimed that school performance is judged against educational targets.

With only a few notable exceptions (in one school performance is judged on “financial return per classroom”), explicitly business-like targets were by no means dominant. For-profit (35%) and corporately-owned (24%) schools do report a greater concern with financial surplus than the not-for-profits (9%) but overall, for all school types, educational success (79%) seems to hold the greatest salience.

How schools judge their performance was further explored in questions related to benchmarking.

As the chart shows, the majority of sampled schools engage in benchmarking of one form or another. It is not, however, solely the prevalence of benchmarking that is revealing, but also what schools benchmark against. Benchmarking covers not only academic performance (73%), but also takes in criteria such as fees (71%), pay and conditions (63%), facilities (39%) and teacher qualifications (25%). For one particularly disenfranchised respondent, benchmarking even extended to “crude comparisons” (his words) of the number of tennis courts, the size of the swimming pool and the number of seats in the auditorium.

Moreover, the small relative differences between what gets benchmarked suggests that measurement of school fees (71%) and pay and conditions (63%) matter to a similar degree as academic performance (73%). Profit may not be a primary success factor (as in Chart VIII) but the economics of education clearly matter. Schools are seemingly concerned with their position in the market vis-à-vis school fees, the marketability of teacher qualifications, the prestige of school facilities and academic performance; an observation that highlights the multiple and potentially conflicting priorities placed on school Heads.

With regard to the extent to which international schools are held accountable through performance metrics, the questionnaire asked participants to indicate whether they use parent and student satisfaction questionnaires:

A full 80% of all schools within the sample undertake annual parental satisfaction surveys, 62% undertake student satisfaction surveys.

Of note, both parent and student surveys were undertaken in more of the schools than teacher satisfaction surveys (56%; not shown above) — I leave the reader the judge the implications of this.

Business Tools

Finally, the questionnaire asked schools which, if any, business tools they commonly use.

Aside from SWOT Analysis, a tool arguably familiar even to high school students, it is apparent that few of the tools common in the commercial world seem to have (yet) found regular use in international schools. Also revealing is that, with the exception of SWOT and formal market research, a significant proportion of Heads were unsure what many of the listed tools actually were — suggesting that Head’s focus remains broadly educational, and rightly so.

Interestingly, differences between adoption of business tools across school types were marginal. Heads working in corporately owned or for-profit schools were no more aware of these tools than those working in not-for-profit schools. The exception, again, being SWOT Analysis. Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, SWOT is used by a greater proportion of not-for-profits (81%) than for-profit (67%) or corporately owned schools (69%) — though I suspect this represents the greater maturity of many not-for-profit schools as compared to the relative youth of many for-profit/corporate schools.

Final Words

On the one hand, specific business tools and practices were not as common as more educational ones — pedagogy remains the priority. On the other hand, there may be limited commercial pressure (only 18% of the sample have profit targets) but the widespread use of parent surveys (76% of all respondents), especially as compared to the use of student and teacher surveys (57% and 54% respectively), suggests that international schools are ‘marketised’.

Further, it is evident that performance management, and benchmarking, are features of international schooling. Teachers are subject to review, appraisal and, whether desired or otherwise, are contracted for terms less than their average tenure.

By no means is the intent of this article to suggest that any of these practices should or should not be adopted. What I offer is merely a reporting of the data as found. Hopefully though, the data is useful for those of you charged with school improvement. In this increasingly professional space, it points to ways in which you might judge whether your school is ‘good enough’.

Further Reading

The economics of international schooling are explored here.

This article by Piety Runhaar covering human resource practices in schools also makes worthy reading.