This was an uncomfortable article to write.

But it’s time.

It’s time to get comfortable being uncomfortable, that’s where the growth is.

The fact is that international schools are a source of (white) privilege. Privilege for its administration, privilege for many of the Western teachers they employ (emphasis on Western here and I include myself in this!), and privilege for the students and families that attend them.

When I first started working in an international school I remember how exciting it was. I’d come from a working-class background and all of a sudden I found myself working in a private school environment. Families owned international businesses, or were doctors, or owned fancy restaurants. Families were able to ensure their children had their own (often high-end) laptops and phones.

Families were present, at least financially.

It’s interesting because in saying this I also think the school I currently work in is modestly privileged (relatively)… Many families scrape together all they have in order to give their child all of the opportunities that perhaps they didn’t have. Students regularly turn down the opportunity to take part in trips to other cities in Thailand because their families have already stretched their money as far as they can. Students sometimes have to move to nearby schools part way during the academic year because they are unable to afford the ongoing costs. On a sliding scale, in which on one end there are schools that promote themselves as precursors to Ivy-league or Oxbridge institutions, charging vast sums of money for the children of the ‘global elite’ to attend, we are much closer to the bottom than the top.

But make no mistake, these are still students that are privileged.

Many families of international school students use the privilege they have accumulated or acquired to send their children to international schools, in the hope that they will be able to get into some of the best universities and be afforded the opportunities of a good life.

Although I didn’t have any financial wealth to speak of, when I first entered the international school market I did have something that made me just as privileged, that didn't cost me anything… I was white, I had a ‘white’ education, and, as a ‘Native-Engish Speaker’, I had a ‘white’ accent.

Racial privilege and implicit bias has been accelerated to the forefront of public attention with the Black Lives Matter movement and just recently with the events at Capitol Hill. We cannot deny that being white means we are judged positively, punished leniently (or in many cases, not at all!), and afforded opportunities more easily because of this single fact.

Many international schools have historically been headed up by white, hetero men, and are derivatives of white, wealthy (private) schools. The curriculums they offer have also been predominantly designed by white, Western men. If we think of our national schools as ‘white’, I think that international schools have historically been, if possible, in an even ‘whiter’ league of their own.

One of the small examples of white privilege that I have recently experienced comes to mind in my current role in university guidance, where I am constantly helping students to grapple with the vast differences in how they must prove their English language proficiency for university admission for the big university destinations (UK, US, Australia).

Universities offering English-medium programmes can differ greatly in terms of what students need to do to prove their English language ability. It’s interesting, because for many international school students, even though they may not be classified as a native English speaker (in my case the majority of students are Asian), their first language may in fact be English. Many of them have spent their whole education in an English medium school, they may speak English at home and conversationally with their friends all day, every day, but because they are not living in a ‘native-English speaking’ country, they still have to prove (and pay for) their ability to converse and write in English, despite many of these students articulating themselves far better than me - and indeed potentially better than many native English speaking students graduating from schools across the UK.

On the other hand, a white Western student who recently returned to the country of their passport, despite only ever being schooled in non-native English speaking countries, and having identical education experiences to many of my Asian students, did not have to provide any proof of their English ability in order to attend university. Apparently being white (and having a white name) meant that their English must be good enough!

You can also see the whiteness of the international school market in how it is presented to the world and how it attracts new customers. The brochures and advertising that deliberately has white or ‘whiter’ biracial students front and centre in promotional photographs - even if these students don’t represent the majority of students. Because as an international parent, you want your kids to become whiter, because being whiter opens doors.

Despite it being increasingly clear for me to see the ‘whiteness’ of international schools, much like starting to clean the smears from my glasses, I fully acknowledge that perhaps I didn’t remove these blurs soon enough. The scarcity mindset which invades much of Western culture - that there’s not enough success, opportunity, admiration, to go around - can make us cling on to what we have, for fear that someone else could take it.

For many international school teachers, when they step into these roles they have a door opened to privilege that they may have never seen and most likely don’t want to let go of. I include myself in this when I say that whilst this is not the world I came from, I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t a world that I wanted to stay in. As a result, we become blind to the privilege that helped us get (and remain) there. We don’t closely examine the recruitment policies or the barriers faced by non-white educators working or aspiring to work in international schools, because it doesn’t affect us. We don’t recognise the struggle of others, and therefore become complicit in ensuring that the systems in place that discriminate against people of colour whilst simultaneously rewarding whiteness, remain firmly in place.

The problem is not staying in this world, but not speaking up or bringing awareness to the lack of diversity that they are built upon.

A recent podcast I listened to I think summed it up perfectly… it said that (racial) privilege is very much like a strong sea current; it’s easy to recognise when we are struggling to swim against it, but it’s not so easy to recognise when we are getting pushed along by it.

It’s time to develop the ability to feel and recognise the difference between the two and to reach out and grab hold when others are being carried away by the tide.

Just because we can’t feel the current, doesn’t mean that it’s not there.

INTERESTED IN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLING?

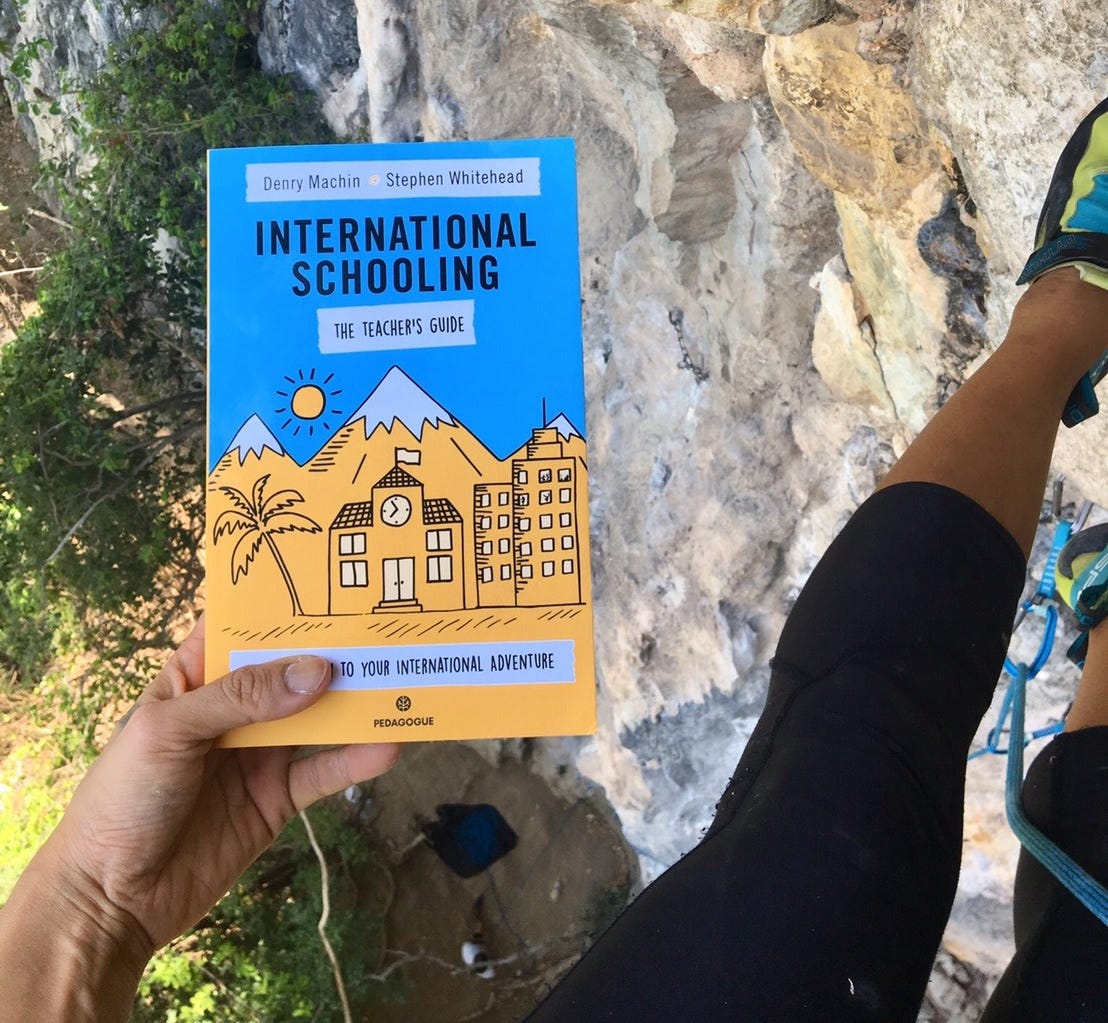

The Teacher’s Guide is getting around! Seen here up a cliff face in Thailand. When we said ‘a companion to your international adventure’ we didn’t quite mean literally!

Grab a copy to take on your own adventure.