THE FUTURE OF INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION

Distinct from, but related to, their ‘International Schooling: The Teacher’s Guide’ book, Dr Stephen Whitehead and Dr Stephen Whitehead consider the future of international education in light of changes brought about by Covid-19. Part Two of this article can be accessed here.

THE FUTURE OF INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION

Lead Author: Dr Stephen Whitehead

Contributing Author: Dr Denry Machin

Facts and Post Covid-19 Speculations

Unless you are in your 90s and can remember World War II – and we don’t think EDDi has any readers quite that old - then you are living through the greatest global crisis of your life. Like WW2, by the end of it you, like everyone else, will have a story to tell; maybe tragic, possibly funny, perhaps just plain bizarre.

No one will be able to claim they’ve lived through Covid-19 without it touching their lives in some way. That is the first certainty to come out of all this. The second is that Covid-19 will be with us for the rest of our lives and the lives of future generations.

There is little chance of this current pandemic ending until a vaccine is produced and made available to all 7.5 billion humans. And that won’t be happening anytime soon. Even when a vaccine is produced and made available, Covid-19, like the flu, will evolve, adapt, and recreate itself, never ever allowing humans to safely assume the risk has disappeared. Like measles, Covid-19, or its descendants, is destined to be part of the human story from hereon.

That is the factual scenario upon which we at EDDi are attempting to predict the future of international education.

Everything Changes, Nothing Changes

When ‘big events’ happen, it is tempting to say ‘nothing will be the same again’. We’ve lost count of how many times that bold declaration has appeared in recent months. Well, big events have happened throughout history and while they’ve always brought about some change in the human condition, never have they changed the core aspects of being human:

Willingness to put self and family first

Desire for a more comfortable life

Preparedness to make sacrifices for one’s children

Cultural myopia mixed with cultural curiosity

Need for social connection and community

Inability to learn from history

These six core human characteristics are inviolate and universal. We know for sure, that by 2120 very few will be alive who remember the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, and even fewer will be worried about it. Indeed, humans in the next century will no more concern themselves with Covid-19 than humans of the early 21st century concerned themselves with the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-20.

Consequently, what we can safely predict is that humanity will suffer more pandemics and global crises in the future, fatally fail to deal with them appropriately, yet blithely if not optimistically continue to live as if its future was assured, or at least under our control. The evidence for this statement is all around you.

Despairing of human intelligence as this might make you, overall it is excellent news for educationalists.

Globalisation

The six core human aspects identified above are, when taken together, the drivers of globalisation. Which is why humankind has been slowly globalising itself ever since humans walked out of Africa some 200,000 years ago.

If the Black Death, numerous plagues, two world wars and the Spanish Flu, couldn’t dissuade humans from their quest for globalising the world’s community, then certainly Covid-19 isn’t going to do it. There is no reason to believe a relatively ineffectual pandemic such as Covid-19 will put an end to the globalisation impulse. Indeed, if anything, rather than putting a brake on globalisation, Covid-19 is going to give it an enormous spurt. Imagine most of humanity in forced lockdown and isolation for weeks, or even months. What is the likely response of humans when they get released? Yes, they will embark on one enormous credit-card fuelled, spending spree.

The last sentence does, however, contain a warning for owners and managers of schools and universities. It is clear that the Covid-19 induced global recession is going to hurt everyone, especially the middle classes. And it is the global middle classes who have driven the phenomenal growth in international schools. Long before we return to something resembling normality (which could take at least a decade), most ordinary middle-class families will be hurting bad, financially. Their credit cards and bank loans will be maxing out. Hundreds of millions will have lost their jobs.

Just how badly individual countries and regions are going to be affected by the financial consequences of Covid-19 is impossible to predict, but we know it will be devastating; one estimate suggests global economic growth with be cut by half. The UK government is forecasting a 35% plunge in Britain’s GDP during the middle of 2020, with unemployment rising to 2 million. The USA would, by contrast, welcome just 2 million unemployed, faced as it is at time of writing, with over ten times that number already registered unemployed and rising daily. Even the hardy German economy is facing recession this year. The IMF predicts Latin America and the Caribbean to have zero growth at least until 2025, with no growth across Asia for the first time in 60 years. China - the country that has come to symbolise the aspirations of a globalised world and a newly empowered Asian middle class – is already experiencing a shrinking economy for the first time since 1992.

The one bit of good news in all this is that the whole world is affected. We are all in it together. Yes, many commentators are predicting that this crisis will tilt the global power axis even more firmly towards Asia, especially China, which may be true, but no country gets out of this mess wholly intact.

There are no winners in Covid-19 - only different degrees of loser.

Education a Loser?

Humans react in a fairly predictable way when faced with great uncertainty and threat, and, economically, their first reaction is ‘aversion behaviour’. This impacts immediately on all core industrial sectors, leading inevitably to short-term hikes in poverty, declines in income and wages, loss of human capital, and infrastructure deterioration (see figure 1).

https://www.cgdev.org/blog/economic-impact-covid-19-low-and-middle-income-countries

Unfortunately, the biggest loser in terms of production, will be education. The UK Office for Budget Responsibility predicts education will suffer a 90% drop in output during the middle of 2020, greater even than the hospitality and transport sectors. The same level of loss is already apparent for international education, with international schools and universities now closed in most every country with no clear indication as to when they will reopen. Indeed, higher education looks especially vulnerable. In the West, billions of dollars are going to be lost to the sector, not least because international students from China and a host of other countries are cancelling enrolments. Many higher-ed staff on precarious contracts have already lost their jobs. That said, dire as the HE situation is for the UK, Europe and the USA, at least governments will do all they can to ensure no university actually goes bankrupt and ceases to operate.

The same cannot be said for independently owned international schools and universities.

CAN ALL INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS SURVIVE?

1. The Location Variable

The first variable any international school owner or principal needs to factor when considering long-term operational survival possibilities, is location. And we are not talking here of how well or not a country has thus far, survived Covid-19 in terms of infections and death rates.

For example, if we consider how effectively Asian countries have responded to the Covid-19 pandemic then six stand out above all others: Vietnam, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, Japan, South Korea. However, the top six look rather different if we consider which countries are least likely to be economically affected by the pandemic: China, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia. In Asia, the worst affected country/region economically will be Thailand, closely followed by Hong Kong.

Eight more important variables are:

Population growth (unplanned pregnancies will rise as a result of the lockdown);

Technological adaptation (AI will play an increasing role in output and addressing human resource problems);

The quality of health care (ability of a country to resist further Covid-19 epidemics);

Reliance of an economy on Small-Medium Enterprises (more vulnerable to bankruptcy);

Quality of education (adaptability of the workforce);

The robustness of a country’s citizenship to handle hardship (e.g. Vietnam stands out here);

The value a population puts on private education and preparedness to pay for it (e.g. China’s big plus);

The willingness of a government to follow the IMF’s stimulus and liquidity recommendations.

If we focus only on the international education market, factor in the number of international schools in a given country plus the risk factors highlighted by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, together with the above eight variables, then what emerges is a list of ten countries where international schools are most likely to survive the Covid-19 pandemic.

China

South Korea

Taiwan

Japan

UAE

Vietnam

India

Malaysia

Singapore

Indonesia

Of course, this is not to suggest that any of these ten countries are simply going to carry on where they left off on January 1st 2020. They are each going to suffer economic hardship. The point is, as far as international education is concerned, they are more likely to bounce back quickly because they have the human, political, cultural and technological resources to do so.

Much hope rests with China. If that country is able to quickly emerge from the pandemic and return to something resembling ‘normal’ production, then the economic benefits will be felt immediately across the Asian region, and eventually the world. This, in turn, will act as an impetus for international schools both directly (in terms of enrolments of Chinese students) and indirectly (in terms of improved local economy).

2. The Ownership Variable

There are over 11,500 international schools globally, of which perhaps less than 1% are owned by the big players: GEMS, Nord Anglia and Cognita. An even smaller percentage are members of a Western private school franchised operation: e.g. Dulwich, Harrow, Shrewsbury, Brighton, Repton, Marlborough. Of the remainder, perhaps 5% are (part)owned by global corporations which have some presence in the international school market (e.g. New World Development, Hong Kong). Then there are the single site operations; prestigious, long-standing, possibly not-for-profit, international schools enjoying significant support and investment from local businesses, NGO’s and the school community – most countries have at least one such school.

While few can claim 100% accuracy when it comes to predicting business trajectories, it seems reasonably safe to assume that the above will have the resources to ride out the depression which follows in the wake of the Covid-19 tsunami.

However, the vast majority of international schools are not corporatised, they are single owner operations, perhaps one of several schools run by the same family or company. These schools enjoy varying levels of stability. To what extent such schools can survive is very likely to depend on the quality of the owner’s relationship with their bank – or the health of their other businesses.

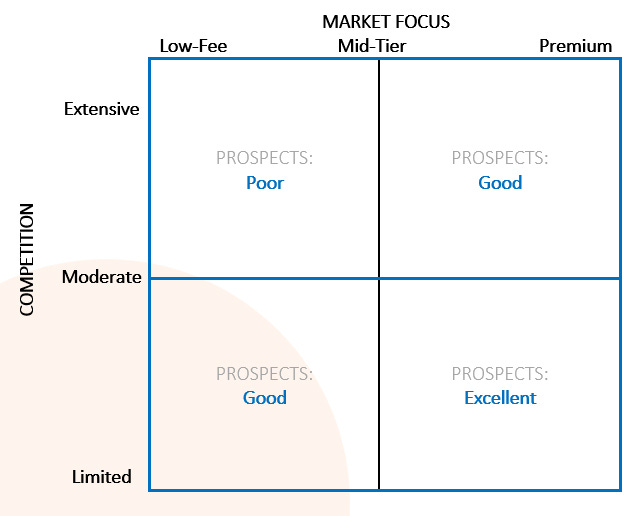

Below we offer a simple matrix to test whether or not an international school is vulnerable over the next two to three years. On the X-axis is market focus, the extent to which a school is considered premium (higher fee) or low-fee. On the Y-axis is the competitive environment, from limited (few competitors) to extensive (many competitors).

Whilst simple, this matrix could be used to ponder a school’s prospects. In our estimation, those single owner international schools in competitive markets with lower fees are most at risk. However, what will work in the favour of some, notably those schools with a high standard reputation but middle-tier fees, is that they very well may take parents from the more expensive prestigious international schools operating in their vicinity; e.g. parents seeking to reduce their private education expenditure but not wishing to return to the state sector.

All things being financially equal for an individual school, the big winners here might be middle-tier schools. Market growth was already favouring them, with newly monied but not ludicrously wealthy parents being the largest source of international school growth. Whilst the premium schools will likely pick up the ‘returnees’, local students now preferring to be educated at home rather than in Western boarding schools, middle-tier schools may attract local nationals for whom the premium schools are now financially out of reach. These schools might also benefit from closures lower down the market; as low-fee schools go out of business, parents who do not wish a return to state education may be forced to look towards middle-tier schools (at least to those with affordable fees).

What hardly any international school is going to be able to do over the next few years is raise its fees, at least not substantially. Therefore, in order to maintain previous standards of delivery and facilities, further investment will be necessary. Those schools who have owners with deep pockets and a willingness to continue investing for a longer-term dividend, will be able to take advantage of this newly turbulent market. By contrast, schools owned by individuals and companies and reliant on bank loans to keep afloat, will struggle. Many will not survive the next two to three years.

3. The Flexibility Variable

Faced with a crisis of any type, it is time to ditch the old assumptions and think creatively. International education will now have to do precisely that. An example is Durham University, one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in the world. On 17th April, right in the middle of the UK’s grave Covid-19 emergency, the university announced plans to significantly reduce face-to-face lecturing, to cut “live” teaching by 25%, and to “invert Durham’s traditional educational model” based on residential study, with one that places “online resources at the core enabling us to provide education at a distance”.

Under these plans, 500 modules will be completely online by the summer of 2021.

Of course, the senior managers at Durham University are not planning for a corresponding reduction in fees. This is about saving money, while (hopefully) not endangering the quality of delivery or indeed Durham’s reputation for academic excellence.

Whatever one’s opinion as to the merits or demerits of such an action, you can be sure most every other UK (and global) university will be paying attention. If Durham are bold enough to execute this policy, then why not any other HE establishment? For sure, Durham are signalling one future for international education – itself a direct consequence of Covid-19. Whether this results in a wholesale shift in HE delivery from limited online provision to massive online provision, remains to be seen.

Of course, it not so easy for international schools to go completely or even partially online. As we discuss below, the fall-out from parents concerned at paying high fees for online teaching has already reached the boardrooms of even the Big Players. But international schools could offer a compromise.

An example would be in secondary schools, where most older students are well capable of self-directed online learning. Here, a school could offer a partial discount to parents who are willing to have their child remain at home for one day a week and study online, so long as there is tutor guidance and a fully integrated online module for the student to follow.

It could also be that some secondary schools change the way they deliver learning. As already happens in some low-fee schools, perhaps a narrower range of courses is offered face-to-face, augmented by online delivery of a broader curriculum. Maths gets taught face to face, but for those students wanting to study, say, psychology, this is offered via an online platform of some form.

Further options for cost cutting are more traditional: increasing class sizes to, say, over 30, and reducing the biggest cost in all schools – teacher salaries and administration.

None of this will be pleasant, mostly it will be downright painful. But for the most vulnerable international schools, none of the options look good.

First time reader?

Welcome. Join hundreds of other fine people and subscribe for free to get fortnightly educational research, news and reviews, all neatly summarised

Head to the About EDDi page to learn more and sign up.

MARKET PROSPECTS WHEN THIS IS OVER

Understandably, there is a growing speculation as to what the global economy will look like once Covid-19 crisis eases down: will people with the means spend more, less or the same as pre-Covid?

Aversion behaviour is unlikely to last. Already, China’s airlines are poised for what is being labelled ‘revenge travelling’, with bookings soaring ahead of Labour Day Holiday (1st May). Certainly, it seems safe to predict that across Asia at least, the desire for spending on some luxuries will still be there, if not heightened. However, it may be different in the West. There are some indicators emerging out of France, the UK and parts of the USA, of people wishing to use the Covid-19 experience as an opportunity ‘to rediscover a more simple lifestyle’, one which inevitably will mean less disposable income, but also a more healthy and sustainable existence.

Which then begs the question is international schooling a luxury or a necessity?

How individuals, families and populations answer that will determine the immediate future of international schooling post-Covid-19. Prior to the pandemic and for at least a decade, the answer has been ‘a necessity’. Driven by globalisation, generational competition for the best jobs, global opportunities for the better educated, a rising global middle class, declining quality and inadequate state education, expansionist international schools and an army of (mostly Western) teachers, growth has been phenomenal.

But will it continue?

One lesson that has been learned is the impossibility of home-schooling for a nation. Much as parents love their children, they’ll be mightily relieved to see them back in the hands of the teachers, Monday – Friday. Regardless of ongoing social-distancing rulings in different countries, we can be confident that governments will be ensuring education is one of the first core services to get back to normal.

Secondly, there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that the vast majority of international school parents are planning to switch back to their respective state education systems. Indeed, with economies in freefall around the world, state education looks decidedly precarious. It certainly is not going to be improved by a decade of zero growth, such as is forecasted for Latin America and the Caribbean and could be experienced across much of the world.

Therefore, our estimation is that most every parent who can afford to do so, will continue to send their children to their designated school. However, as we suggested above, there could be a growth opportunity here for those lower-fee schools, offering an international curriculum, good standards, but at a more affordable price. So long as they have the space to take the extra children, their local reputation is sound, and they have the funds to weather the next 12 – 24 months, they could be beneficiaries.

A second market opportunity emerges for the big-name international schools, especially the prestigious franchise operators. If such operations develop branded online teaching and learning products, both for existing and new students (part-time and full-time) then the windfall could be significant. Indeed, the income (and profits) generated in Asia, especially China, by online education providers was staggering even before Covid-19 closed down all the schools. Arguably the most famous private school in the world, Eton, had already gone down this road long before Covid-19 hit, and its governors are no doubt now delighted they did so.

What Covid-19 has done is normalise online learning. We can already see how it will become further normalised once big-name universities engage with it wholesale, as Durham University are planning to do. Out of that normalisation will emerge a greater willingness to adopt online learning not as a total replacement for face-to-face classroom teaching, but certainly a legitimate supplement and possibly a part-replacement, at least for older students in secondary schools and colleges.

What are the staffing implications?

As we write, there will be many thousands of private schools and universities around the world relying for income, and therefore keeping financially afloat, only on the fees they’ve received thus far this academic year. Unfortunately, as is already becoming apparent, many parents are complaining at what they see as a great injustice: fees being taken for a service not received. Understandably, parents paying, say, US$10,000 in tuition when only online classes are available, do not consider it justified.

This conflict puts international school owners and managers in a bind. On one hand they cannot afford to lose the goodwill of their clients, the parents. On the other, they are committed to paying staff salaries even while the school is closed. The most favourable option for any international school in this position, and that is probably most of them, is to offer some discount on current fees. However, the question then becomes ‘when to offer such a discount?’ Should the discount be immediate or should it come later? If it is immediate then it certainly will allay the concerns of cash-strapped parents. But if it comes later, say in the next academic year – a ‘loyalty’ discount for those parents who continue to send their children to the school – then this works both in favour of the parents and the school budget.

What seems the least favourable option is to do nothing – for an international school to simply try and carry on as if nothing has happened. Huge swathes of the global middle class have been in lockdown for weeks if not months, many families relying on government ‘furloughs’ in order to pay their monthly bills. Even the big banks have had to come to the rescue, offering interest-free overdrafts and much more flexibility on loans. It will look very bad for the international schools if they don’t also apply some flexibility. In this situation, a little will go a long way, while nothing will be remembered for a long time.

While each school will be faced with its own unique set of financial and budgetary considerations, the one variable that doesn’t change for any school is the need to employ teachers. And for prestigious international schools, that means Westerners.

But could this reliance on Western teachers change, post-Covid-19? Who knows what travel restrictions will be in place at any future point? If teachers are not immediately physically available to undertake international travel, then schools will need to look elsewhere for staff. One option is to employ more local (or regional) teachers, so long as they have the language skills and qualifications. However, employing too many local/regional teachers is unlikely to go down well with the parents, paying primarily for a ‘Western educational experience’.

There is factor which works in favour of international schools, especially those not situated in the USA or Europe. And that is the clear divide between how well the West has been handling Covid-19, and how well the rest of the world did. If you’re a Westerner and been hunkered down in countries such as Taiwan, Thailand, UAE, or Vietnam while Covid-19 wrecked its global havoc, then you’ve been most fortunate. It has mostly passed you by. Unlike for your fellow citizens in the UK, Spain, Italy or the USA. This could spur more newly-graduated Westerners to look elsewhere for their career pathway in which case, international school teaching is an obvious option.

Of course, whether or not international schools will need all these new teachers largely depends on how quickly the global economy corrects itself and comes out of the depression. At the time of writing, the market prospects, and therefore the job prospects do not appear evenly spread around the world. Due diligence both on the part of prospective teacher and schools, seems in order.

The Lessons

While the Covid-19 death toll has been tragic, equally despairing has been the rise in xenophobia and blatant racism fuelled by Covid-19.

The first signs of an anti-Asian sentiment in some sections of the population emerged in the West, weeks before Covid-19 took hold. In the UK, Asian and Chinese-looking students were verbally abused in the street, and in some instances, physically attacked. Similar incidences were repeated across Europe. In the USA, it has become so bad that it is now claimed “dangerous to be an Asian-American” with thousands of reports of verbal harassment, shunning and physical assault. It has been described as an ‘epidemic of hate’, with Asian-American women especially vulnerable. So bad has been the racism in the USA, that it spurred the Be Cool 2 Asians campaign, designed to eradicate harmful notions that Asians could be responsible for the pandemic.

But Asia has little reason to smugly condemn the West when it comes to racism. By the middle of April, numerous reports were coming out of China of foreigners being denied service in restaurants and shops, and of Africans being singled out for racist treatment in the southern city of Guangzhou.

All of which batters the notion of racial progress and greater acceptance of minorities, while making the concept of ‘global citizen’ at, best, tenuous. Right now, global citizenship is in short supply.

It will be a first task of all international school teachers to redress this insidious xenophobia and racism once normal teaching resumes. Fine words, mission statements, curriculum objectives, and liberal aspirations are excellent but Covid-19 has revealed just how thin is the veneer of human tolerance and empathy and how easily does irrational hatred of the ‘other’ emerge in humans.

Which leaves us with a final observation.

Humans are not a nice species; maybe we deserve Covid-19. There is certainly a sense we had this coming.

Let us hope we can learn the lessons Covid-19 is giving us. If so, international education, from schools to universities, will have a key part to play in doing just that.

Enjoyed reading? Got questions? Part Two of this article can be accessed here.

Lead Author: Dr Stephen Whitehead. Read more of Stephen’s work on Medium or purchase his books on Amazon.

Contributing Author: Dr Denry Machin. Read more of Denry’s work on Medium or purchase his books on Amazon.

How can you help? Subscribe or Share

Every fortnight EDDi provides vital educational research, summarised. EDDi saves you time and money, keeping you professionally engaged and up-to-date.

To keep EDDi alive we need subscribers. If you like what EDDi offers, please share with colleagues. Help EDDi on its journey by sharing.

Interesting read, thanks!

Concerning The list of ten countries where international schools are most likely to survive the Covid-19 pandemic, Is this list in order of significance?

Also, ”Much hope rests with China”...well said. As an international teacher in Singapore I see evidence of this...not only is the absence of Chinese nationals affecting enrollment but tourism as well. Here in Singapore, there seemed to be a mass exodus of Chinese nationals—one of major centers of revenue, Orchard Rd, was relatively empty well before the travel ban and circuit breaker.

This was solid read, thanks for your predictions and analysis.